Cemetery in Billerbeck

The missing graves at the Jewish cemetery in Billerbeck: the Albersheim-Eichenwald family history and the Shoah memorial

Gateway to the

Jewish cemetery

in Billerbeck

Albersheim-Eichenwald family history

Four generations

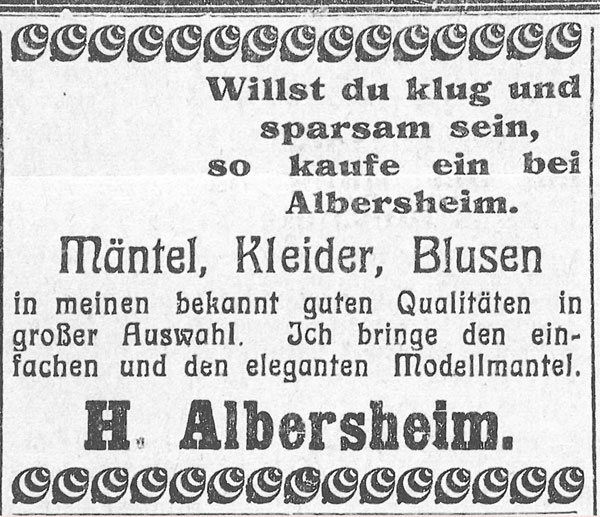

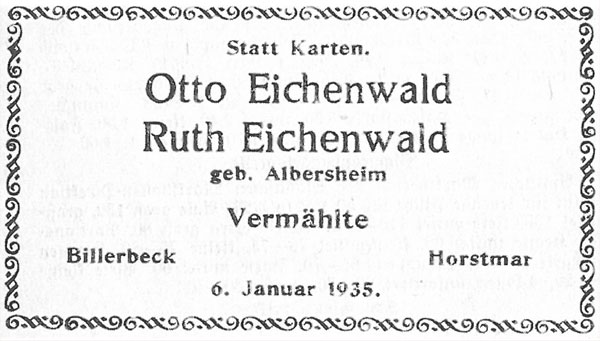

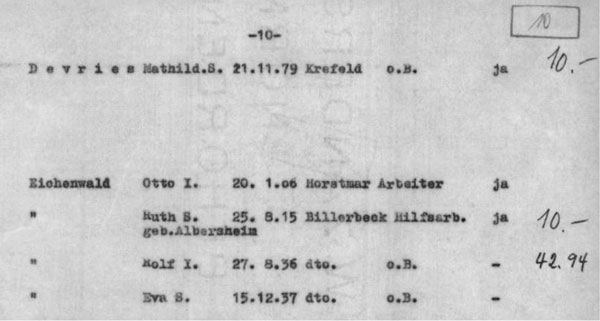

Ruth Albersheim married Otto Eichenwald (*1906) from Horstmar in 1935. The couple had two children: Rolf-Dieter (*1936) and Eva (*1937). The increasing disenfranchisement of Jews by the National Socialist regime and their ousting from economic life forced the Albersheim-Eichenwald family to give up the business at the end of September 1938. The family moved to Krefeld.

Albersheim-Eichenwald family in Krefeld, turn of the year 1940/41: from left to right: Rolf-Dieter Eichenwald, maternal grandparents Josef and Selma Albersheim, parents Ruth and Otto Eichenwald with Eva Eichenwald, and Adele Albersheim, Josef Albersheim’s sister.

Deportation and murder

The founding generation of the Albersheim-Eichenwald family, Heimann and Sofie Albersheim, died in Billerbeck and were buried in the Jewish cemetery in the Berkelaue in 1905 and 1912 respectively. No member of the following three generations was buried in their hometown. What happened to these people, where were they buried? The missing graves reflect the Shoah: the empty spaces in the cemetery point indirectly to the murder of these Jewish Germans far from home.

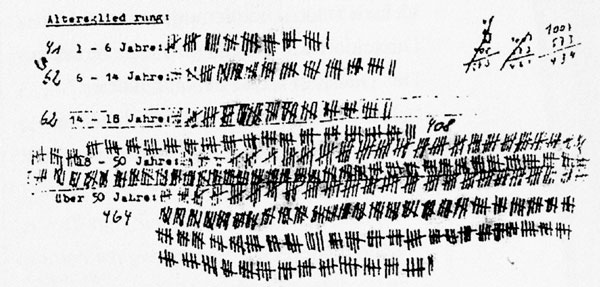

Of the 1,007 people on the Düsseldorf transport, only 98 survived. The members of the Albersheim-Eichenwald family were not among the survivors. They were not given an individual grave, but were shot and buried in mass graves or gassed and burned in extermination camps.

Josef Albersheim, the grandfather of the Eichenwald children, died in January, and his sister Adele in October 1941 in Krefeld. Their deaths saved them from the pending deportation. On 11 December 1941, the grandmother Selma Albersheim, the parents Ruth and Otto Eichenwald, and the children Rolf-Dieter and Eva were deported from Düsseldorf to a Jewish ghetto in Riga in occupied Latvia. Rolf-Dieter was five; Eva, four – she turned five three days after their arrival.

Shoah memorial

Private

After 1945, a Jewish cemetery is no longer just a place of remembrance for the families, but also a place of remembrance for the victims of the Shoah who did not die in their homeland and as a result could not be buried here. The memory that the survivors and those born afterwards have of the family members murdered has written itself into the cemetery’s appearance.

The last burial at the Jewish cemetery in Billerbeck during the Nazi period took place in December 1939. The cattle dealer David Davids (*1867) had died on 11 December 1939. After 1945, his son Julius Davids (1908-1966), who was able to flee from the Nazi regime to South America, had a gravestone erected that gives information on his father’s life. There are also the names of his mother and brother with their dates of birth, as well as the information: “Remained in concentration camp”. The gravestone for the father is also a gravestone for the missing mother and brother.

The vague reference to “concentration camp” as a cipher of “whereabouts” reflects the diffuse knowledge at the time of what had happened to family members. The mother Bertha Davids was deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto at the end of July 1942, where she died in January 1943 as a result of the inhumane living conditions. The brother Albert

Davids was taken to Bielefeld for forced labour in July 1940 and deported from there to the ghetto in Riga on 13 December 1941, where he disappeared from trace.

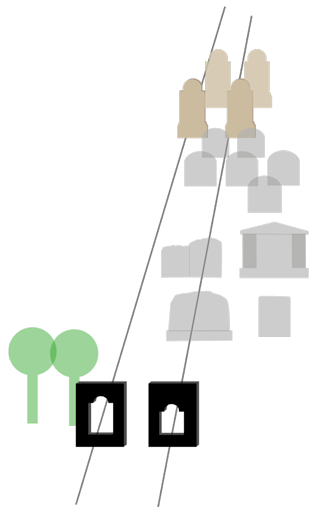

The memorial in front of the cemetery is aligned with the gravestones of their maternal great-grandparents, Heimann and Sofie Albersheim, which are located at the back of the cemetery. The visual axis connects the generations, although the graves of three generations who could not be buried in Billerbeck are missing. They are represented symbolically by the memorial stones.

The gravestone for David Davids (+1939) reflects the sepulchral culture of the mid-20th century: a rectangular granite stone with a polished front, exclusively in German, the only Jewish symbol being the Star of David. The design of the gravestone suggests extensive cultural and social integration into well-to-do society.

Public

A public memorial to the victims of the Shoah came comparatively late in Billerbeck. While the traditional memorial to the “war dead” dominated until well into the 1980s, there was not a memorial to the “victims of war and tyranny” until the turn of the millennium, with the “war memorial” being turned into a “memorial” commemorating both the civilian and military war dead as well as the victims of National Socialist tyranny. A glass plaque (2002) lists all victims of the violent 20th century by name, arranged according to groups of victims, and the names of all Shoah victims, including those of the Albersheim-Eichenwald family, can therefore now be read in the centre of Billerbeck.

In 2005, a private initiative sought to give adequate honour to the cultural and historical site by upgrading the surroundings of the Jewish cemetery in the Berkelaue. A memorial designed by artists in front of the cemetery recalls the fate of the Eichenwald children and establishes a link to the family history. The outlines of the two stone blocks recall the shape of the graves in the cemetery that date from the 1920/1930s. The outlines of the clearings in the middle of the ashlars take up the shapes of the older gravestones, recognizable by their round arches.

Idea and text: Matthias M. Ester MA, Münster

Drawing of cemetery gate: Prof. Jörg Heydemann, Billerbeck

Photos 1-14 and sources: Veronika Meyer-Ravenstein, Zersplitterte Sterne, 2nd ed., Dülmen 2020; Bielefeld municipal archives, Kriegschronik 1941; Andreas Wessendorf, Innovation Office; Matthias M. Ester MA;

https://www.statistik-des-holocaust.de, https://deportation.yadvashem.org/

Design and diagram of site plan: Kerstin Schneider, Innovation Office